Thanks For The Memories

About two years ago I started, and almost finished, a long blog post about how important it is to remember things. Then I forgot about it.

I wish this were a joke, but it’s not. In 2022, I wrote over 1400 words prompted by a Twitter discussion I’d seen about memory. Then it immediately slipped my mind. I’ve now returned to that post and finished it.

The changing debate about memory and teaching

Over the last twelve years or so, attitudes about the importance of memory for learning seem to have changed. When I was training to teach, two attitudes seemed to dominate:

Memory was unimportant. Recall was "lower order thinking" and the bottom of Bloom's taxonomy. Good teaching encouraged pupils to understand and think independently and creatively.

Memory was important, but what determined how well pupils remembered was how interesting the lesson was, and how connections were made between different topics from lesson to lesson. There was no need to consider what you wanted your class to remember or test that they remembered it.

In both cases, it was often assumed that asking your pupils to commit anything specific to memory, or testing them to see if they had done so, was seen as boring, ineffective and possibly even cruel. Worse still, it was often thought that focusing on memory would somehow undermine understanding and prevent "real" learning.

Since then, it's been more widely understood that what you remember, and how fluently you can recall it, is very important for understanding and "higher order" thinking. I think Daniel T. Willingham's Why Don't Students Like School? may have been the key text in changing attitudes. This change is now reflected in how exams are constructed and what inspectors expect to see in a curriculum. I suspect this is what has led to a more widespread interest in the mechanisms of memory among teachers. These developments have popularised some practices, such as quizzes to test factual recall, that were once frowned upon.

The above account is mainly based on my experience, and discussions with other teachers. I was aware that there were people, often educationalists and consultants, who either missed these changes due to being out of the classroom or somehow resisted being influenced by them as they happened. At times, it has been painful to watch people who consider themselves "experts" on education fail to grasp what teachers are now doing or why. But, in general, I would say that the teaching profession in England, now has a respect for the importance of memory and that this respect was absent in my first decade of teaching.

Is memory still controversial?

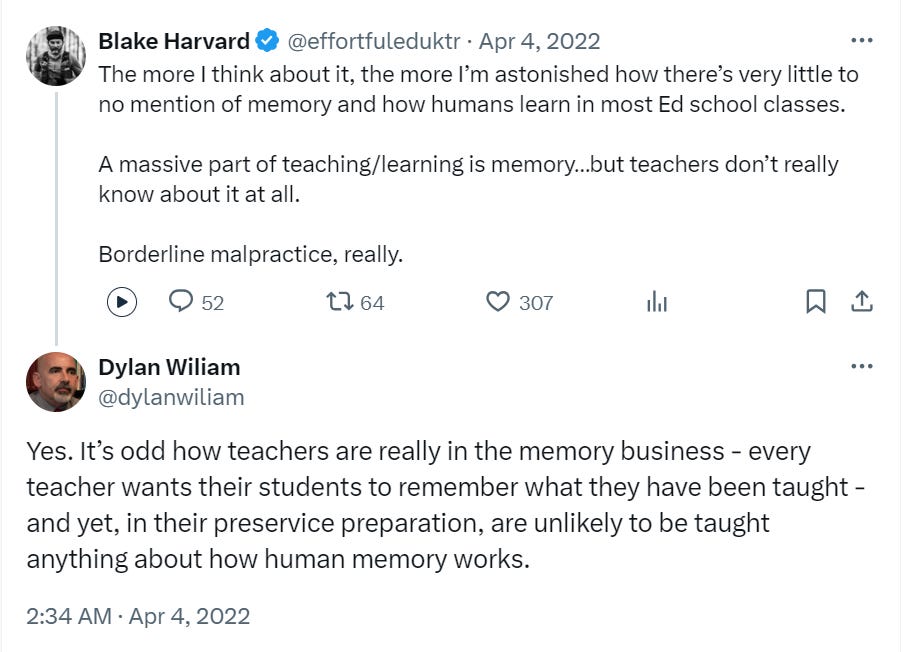

What I have to say in the rest of this post was originally prompted by the responses to a Twitter exchange between Blake Harvard and Dylan Wiliam. They discussed how memory is important for learning.

Reading the replies is an insight into why people have underestimated the importance of memory in education. So much so, that I thought it worthwhile to devote a post considering these ideas. For obvious reasons, I will ignore responses that were:

ad hominems;

pretentious waffle,

assertions that a focus on memory is unsophisticated or incomplete which didn't identify anything lacking or wrong with such a focus.

In addition, there is another category of comments I don’t feel the need to address in detail.

Arguments from The Before Times

There are still people who remain oblivious to the way memory enables thinking.1 Some people believe that we can Google anything we need to know. Others think that we remember things only because they were explained well, or we were interested, or there was something profound or meaningful about the experience of learning them. There are still some who claim that memorising is somehow harmful, or that it is in conflict with understanding. The argument that ignorance, rather than knowledge, helps children develop the ability to work independently is still around.

Just because teachers seem to have moved on, doesn't mean that there aren't a lot of people who haven't, who are still seen as "experts" and who are generally unaccountable for their ignorance. It is depressing to see how many of these people are employed to train teachers. In this post, I won’t address the arguments of those who have not been paying attention, as they have been addressed many times. Instead, I will look at arguments that seem to acknowledge that others have argued in favour of a) memorisation as a goal in teaching or b) training teachers to help kids memorise knowledge.

The arguments against memorisation2

“But what about subject knowledge?”

The strongest argument against teacher training having a strong focus on memory is that it’s more important to ensure teachers are experts on the subject(s) they teach, rather than on how memory works. Training teachers to be experts in generic aspects of teaching is often a distraction from ensuring they know the content of the curriculum. In this case, I suspect it's a bit of a chicken-and-egg argument. There's no point knowing how to ensure your pupils will recall content, if you don’t have any content, but it's also less than useful to be teaching content that will be forgotten.

“But what about feelings?”

Some people see learning as primarily an emotional experience. The idea is that, by being taught something, we either experience pleasure, or have some kind of profound personal experience that changes us. Self-esteem has been mentioned in this context. The problem with these perspectives is that they raise the question of what teaching is for. There’s nothing wrong with entertaining children. However, it's not the point of teaching, and even the best teaching cannot be expected to be more entertaining than the work of professional entertainers. If entertainment were the point of education, why not let your pupils watch cartoons? Or play? Or surf the internet? As for personal growth, it may result from learning. However, if it doesn't result from knowing something new, then what you are talking about isn't teaching; it's therapy. These arguments are not arguments against focusing on memory, they are arguments against teaching. Some teachers want to be children's entertainers or unlicensed therapists. They shouldn't be encouraged.

“But what about child development?”

Some people see theories of child development as conflicting with theories about memory. Some of this can be seen as special pleading for those working with younger children. But I wonder how much of this is the ideological belief that children will naturally learn everything they need to and, therefore, only need to be encouraged to explore. The explicit teaching of specific knowledge is, therefore, unnecessary. Perhaps there is a more scientific, less ideological, version of this argument. However, I haven’t seen how it gets around the fact that there is a lot more experimental support for the psychology of learning than for theories about how children can be encouraged to develop. If there is empirical research showing the effectiveness of learning based on theories of child development, the advocates of these ideas have been remarkably quiet about it.

“But what about relationships?”

It's a constant feature of educational flimflam that, once you claim that education is about "relationships", learning goes out the window. While it is trivially true that how teachers and pupils relate to each other will be important, there is no coherent body of knowledge to be taught about forming relationships with children.3 Until there is, it is completely untestable whether focusing on relationships would be more effective than focusing on memory when training teachers. Additionally, even if relationships make teaching more effective, it is unclear why this would not be a new fact about how memory works, rather than a reason not to focus on memory.

“But what about skills and dispositions?”

Daniel T. Willingham's aphorism "learning is the residue of thought" has been adopted by some as a reason to think that teaching "thinking skills" is the best way to to ensure pupils remember more. This surprised me. It distorts Willingham’s views, and he has written at length about how if you want children to be critical thinkers, it would be better to consider what specific skills are needed in each domain, rather than trying to teach generic thinking skills.

"But that's Cognitive Load Theory"

CLT is an area of empirical research in educational psychology that pays attention to particular facts about how memory works. There now appear to be people who think you can dismiss scientific claims about learning by calling them “CLT” and appealing to some imaginary consensus that CLT is bad. None of these people seem to know what CLT is, or why it is bad. I have discussed a version of this argument before:

Blog post: Can we reject an idea for being too simple?

“It's implicit”

Some have suggested that even if teachers have not been trained or taught about how memory works, this knowledge is implicit in what they have been taught about how to teach. This is possible, but it's not clear where this happens. There were many people in the discussion who thought they knew how memory worked, because they assumed that what they thought was important in teaching (making learning relevant, encouraging students to express themselves, asking open rather than closed questions) must also be good for making memories. I would argue that an implicit theory of memory is more likely to be wrong, because where it comes from is unknown and the research on which it is based is not explicitly identified.

“We know very little about the brain”

This one was a little unexpected. Despite advances in neuroscience, we remain largely ignorant about how the brain works. Therefore, we cannot expect to be able to answer questions about what is important for learning. This seems to be an attempt to obfuscate rather than address the question. Psychologists don’t need to study the brain’s anatomy to study learning. Teaching is not applied neuroscience. In this blog post, neuroscientist Dorothy Bishop argues that:

…at the heart of [educational neuroscience], there seems to be a massive disconnect. Neuroscientists can tell you which brain regions are most involved in particular cognitive activities and how this changes with age or training. But these indicators of learning do not tell you how to achieve learning. Suppose I find out that the left angular gyrus becomes more active as children learn to read. What is a teacher supposed to do with that information?

Conclusion

None of these arguments against the importance of memory to learning provides a coherent alternative. Some are based on a lack of understanding about what learning is, others on an apparent opposition to learning. While there will always be those who claim “memorisation” is not learning, nobody has refuted the arguments for the importance of memory.

Neither of these two tweeters is based in England, so it is likely that many of those who read their exchange will have replied without considering some of the ideas that are now commonplace in England’s schools.

These are not quotations. I am trying to give a flavour of the arguments, rather than identify individual tweets. It may be the case that a more nuanced version of these arguments exists, if so, feel free to present them in the comments.

The exception to this is if you consider the art of psychological manipulation to be a science. It might be possible to train teachers to trick children into doing what they want.

I think, at the other end, early dementia and Alzheimer's are examples of what happens to us when memory fails. Memory is critically important to us and we ignore the ability to remember at our peril.