Why do I write about exclusions?

For some time, I have been writing about pupils excluded from school. I have focused on getting accurate information to a wider audience. Almost all media coverage of exclusions, and almost all political comment on exclusions, assumes that the claims made by activists about exclusions are reliable.

Debate over exclusions and ethnicity has been one area where false or misleading claims have been common. It is often asserted that pupils from ethnic minority backgrounds are more likely to be excluded, but this has not been true for many years1. It is also frequently claimed that black pupils are at greater risk of exclusion, although the last academic year in which that was true was 2018/19. There are concerns regarding smaller, highly disadvantaged ethnic groups, which have higher exclusion rates. However, no good evidence exists that race or racism is important in exclusions. Some pundits are not happy for that to be known. I have found that sometimes it is controversial even to correct false information about race, and I have lost count of the number of times sharing accurate information about exclusion statistics has led to an activist of some description accusing me of racism. This has even happened when I have been challenging overt racists who are using false claims about exclusions to attack black pupils.

The changing picture of black pupils and exclusions

There have been several recent developments regarding black pupils in England. I am not sharing this to be contrarian, or to imply that there are no problems in England's schools related to race or racism. However, much of the commentary about race, racism and black pupils in England's schools is derived from the US, where outcomes for black pupils are still far worse than for white pupils. Commentators might also be influenced by considerations from years ago, when the outcomes in England were very different. Another possibility is that they may have been misled by extrapolating from London. London’s white British pupils are a small, but affluent and educationally successful, minority. The reality is that the latest outcomes for black pupils in England are far from worrying. Of course, nobody can tell from statistics alone whether black pupils are treated fairly, and nobody can reasonably deny that racism exists in England. Nevertheless, some of the most common concerns about black pupils’ educational outcomes now seem misplaced.

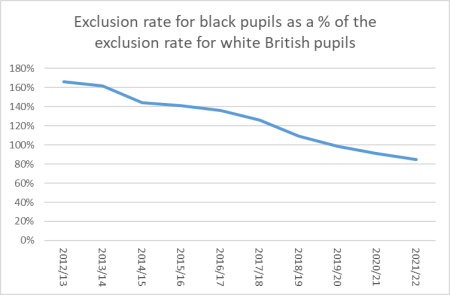

Let me start with permanent exclusions, as this is my specialist subject. As I have mentioned many times, black pupils are no longer more likely to be excluded than white British pupils. In the latest figures (academic year 2021/22) they are noticeably less likely to be permanently excluded. This is a recent development. Just how recent can be seen from the graph below, which shows the exclusion rate for black pupils as a percentage of the exclusion rate for white British pupils. It is also noticeable how relentless the change has been. Although it is a recent development that black pupils are less likely to be excluded than white British pupils, it appears to be part of a long-term trend, not a random fluctuation or an anomaly caused by the pandemic.

We can also look at suspension figures. Black pupils have been less likely to be suspended than white British pupils since 2017/18. And again, there seems to be a fairly consistent trend.

This is also reflected in the figures for attendance at Pupil Referral Units. In January 2022, black pupils were 5.6% of pupils in PRUs, despite being 5.8% of the school population.2

I've focused so far on outcomes related to discipline and behaviour, because these are where we see some of the most pernicious stereotypes. Some online racists will respond to almost any discussion of violence in schools with a comment about black pupils being responsible, even when discussing areas of the country where there are hardly any black pupils. Equally, there are online "antiracists" who seem determined to convince black parents that their children will constantly be in trouble at school and that PRUs are full of excluded black pupils. At times it is hard to work out whether it is racists or self-described antiracists, who are more attached to the myths about black pupils and behaviour.

What is the academic performance of black pupils like?

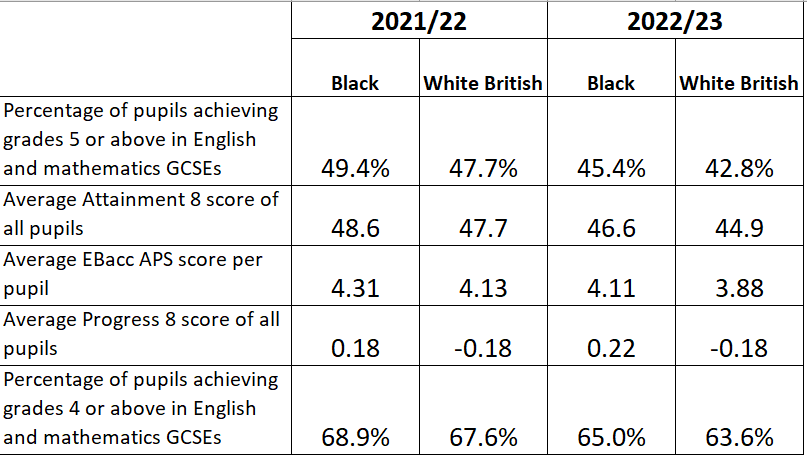

Since engaging with the issue of black pupils’ suspensions and exclusions, I've noticed that similarly inaccurate assumptions are made about the academic performance of black pupils. A recent, but not widely publicised, development was that after pupils returned to sitting GCSE exams in 2022, black pupils outperformed white British pupils on almost every measure. This gap then widened in 2023.

Data from here.

These differences are not huge, but they are enough to be inconsistent with the idea that black pupils are doing badly in British schools. However, a bigger difference can be observed if you take disadvantage into account. For pupils on Free School Meals,3 black pupils dramatically outperform white British pupils in their GCSEs:

Data from here.

One indicator above all others distinguishes black pupils from white pupils (unfortunately I don't have the data specifically for white British pupils). In 2022, 50.6% of black pupils aged 18 were accepted into Higher Education. For white pupils, it was 32.2%. The last time the acceptance rate was higher for white pupils was in 2006.

Why this matters

I've tried as far as possible to present the data without commentary. Therefore, what I have written here could be misrepresented as an attempt to show that there is no racism in schools in England. I do not believe that, any more than I believe girls outperforming boys in virtually every educational metric means there is no sexism in schools. My intention is only to challenge those who claim that black pupils in England have poor outcomes. If I were to add anything more controversial to this, it would be to ask anyone who is convinced that black pupils do poorly in England's schools, why they want to believe this. There seems to be a reluctance to acknowledge the improved outcomes of black pupils in England’s schools. It’s worth acknowledging this to challenge racists who claim black pupils are less well-behaved or less able than white pupils. It is also strong evidence against the belief that educational disparities between broad racial groups cannot change over time. When white British pupils had better outcomes than black pupils, some argued that the only possible explanations for racial disparities were racism, or innate differences in temperament or intellectual ability. Would they still say these are the only possible explanations now that the disparities have been reversed?

There are questions here I haven’t addressed. I haven’t examined why some of these statistics have changed over time. I haven’t looked at different subgroups of black pupils and how their outcomes differ. However, I think these are questions that will be addressed by others, once the fact that black pupils do not have bad outcomes in England’s schools is more widely acknowledged.

The last time that, after rounding, the exclusion rate for ethnic minority pupils was higher than the exclusion rate for white British pupils was the 2010/11 academic year.

The details for these figures, as well as an example of scaremongering about black pupils in PRUs, can be found in this blog post, where I provided the following information:

… the most recent figures on ethnicity and school types (based on the January 2023 school census) do not distinguish between PRUs and other types of Alternative Provision (AP). However, the statistics did make this distinction previously, so we can look at the ethnicities of pupils in PRUs in January 2022. It takes a bit of calculation because black pupils are divided into 3 categories: “black African”; “black Caribbean”, and “any other black background”. If we add up the figures for all three, we find there are 653 black pupils on roll in PRUs. This is 5.6% of the 11684 pupils in PRUs. There are 486517 black pupils in the total school population of 8418013, which is 5.8%. So according to the 2022 figures, that means black pupils are slightly underrepresented in PRUs. If we look at the AP figures from January 2023 we get something similar. i.e. black pupils are slightly under-represented.

Eligibility for Free School Meals, when aggregated for a group of pupils, is commonly used as an indicator of poverty.

This is a brave and important piece of work. Thank you.