UPDATED POST: Is SEND a risk factor for exclusion?

Technically, yes, but probably not in the way you think.

I wrote the original version of this post in May 2023 using data from the 2020/21 academic year. Since then, data for 2021/22 has been published. Following the response to a Freedom of Information request, I can now update the post with the latest data.1

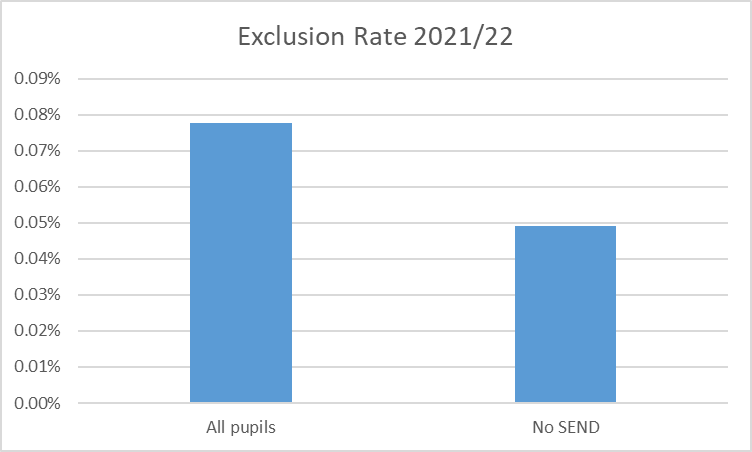

It’s an oft-repeated claim that pupils with Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND) are at risk of exclusion. This is technically true; the exclusion rate for pupils with SEND is much higher than for pupils without SEND.

To some extent, any comparison of small risks is misleading. If a risk is low, then even an apparently sizeable discrepancy can be irrelevant to most of the group affected by the discrepancy. So if we look at the proportion of pupils who are not excluded, we can see that the difference is barely visible.

(Both graphs are calculated from the data available here).

However, that’s a feature of all discussions about permanent exclusions. We talk about something that affects only a tiny proportion of a demographic, as if it were a problem for the entire demographic. Whether a randomly selected pupil is labelled SEND or not, they are unlikely to be excluded, because exclusions are rare events.

There is a much bigger problem with talking about the risk of exclusion for SEND pupils: the willingness of schools to label pupils with behaviour issues as having SEMH (Social, Emotional and Mental Health) needs. While this is intended to be a broad category, covering mental health difficulties and conditions such as ADHD, it is often explicitly linked to behaviour. For example, Camden Council describes SEMH in this way: “Social, emotional and mental health (SEMH) needs are a type of special educational needs in which children/young people have severe difficulties in managing their emotions and behaviour”. Putting many badly behaved pupils in the SEMH category has two effects on the data.

Firstly, it removes huge numbers of badly behaved kids from the “No SEND” category, because of problems that have been identified mainly from the fact that they are badly behaved. For this reason, we shouldn’t think of “No SEND” as the “no disabilities” category; it is better to think of it as the “no problems” category. Pupils in this category are much less likely to be excluded than the average pupil.2 This makes comparisons between pupils with and without SEND somewhat misleading.

Secondly, we can expect the SEMH category to include many pupils who cannot be said to have a disability. Their difficulties are better described as behaviour problems, or patterns of behaviour. Ideally, I would argue that we should throw out the SEND label, as it seems to encourage people to see almost all problems children have with accessing education as disabilities. It should be possible to support pupils with behaviour issues, without implying that those issues are the result of a disability. This seems particularly important as there is research suggesting the most effective behaviour interventions address bad behaviour directly, rather than identifying the causes of bad behaviour.

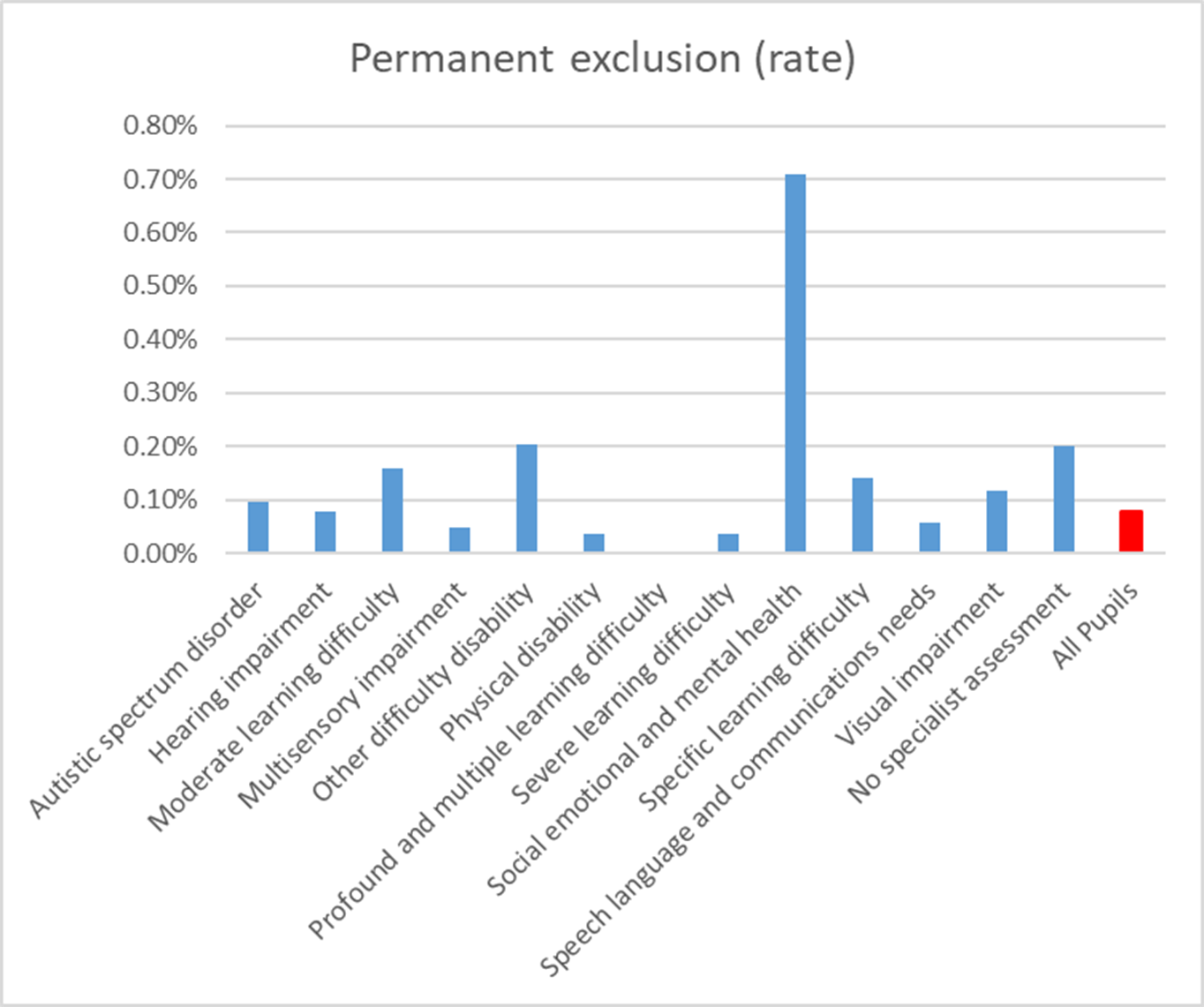

The categorisation of badly behaved pupils as SEMH also means that the majority of excluded SEND pupils are SEMH. SEMH pupils make up 18% of SEND pupils, but 60% of permanently excluded SEND pupils.3 If we treat SEMH as distinct from the rest of SEND, the exclusion rates look very different.4

SEND pupils who do not have SEMH as their primary need have an above-average exclusion rate, but not by a huge amount. And even that is misleading, because of two further facts.

All types of SEND are more likely to be identified in boys5.

I made a Freedom of Information request to get a gender breakdown for the figures relating to SEND and exclusion.8 We can calculate the exclusion rates for pupils with SEMH, SEN other than SEMH and all pupils again, this time also broken down by gender.

Boys with SEND other than SEMH are only slightly more likely to be excluded than the average boy (0.13% compared with 0.11%).9 The difference is greater for girls (0.07% compared with 0.04%), but this is still a low risk of exclusion. It’s tempting to say that only SEMH is an important factor when considering SEND and the risk of exclusion. However, it’s not quite that simple. Different categories of SEND have different levels of exclusion risk, although none of them are anywhere near being as high risk as SEMH.

Again, it’s worth looking at gender, but the number of girls in most categories is so low that I will only present the figures for boys here.

It is worth noting that speech, language and communication needs dramatically lower the risk of exclusion. For boys, Autistic Spectrum Disorder (ASD) also reduces the risk of permanent exclusion. While ASD significantly increases the risk of exclusion for girls, it makes little difference overall. The number of permanent exclusions for pupils with ASD is almost exactly what would be expected from a random sample of the same number of pupils with the same gender balance.10

Despite this, we are often told that speech, language and communication needs and ASD increase the risk of permanent exclusion. The Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists claims that speech and language difficulties are likely to be a cause of behaviour leading to exclusion. The National Autistic Society suggests a link between autism and permanent exclusion by comparing the exclusion rate of pupils with ASD with that of pupils in the No SEND category. Advocacy groups seem happy to publicise problems that don’t exist.

Returning to the question we started with, we can conclude that not all types of Special Educational Needs and Disabilities are risk factors for exclusion. Most of the risk of exclusion among SEND pupils is among those categorised as SEMH. There appears to be a widespread desire to portray excluded pupils as “vulnerable”. This may have led some to portray all SEND pupils as being at risk of exclusion.

As well as updating the data and making small changes in the text where it could be improved, I have made another major change. In the original post, I referred to “SEN(D)” because the data use the term “SEN” and yet the usual term is “SEND”. In this post, I have used “SEND” throughout, even when quoting data that use the term “SEN”.

In the original version of this post, SEMH pupils made up 18% of SEND pupils and 61% of excluded SEND pupils, which shows how consistent the over-representation of SEMH pupils in exclusion figures is.

Graphs based on the FOI response, rather than public information, are in a different font. Feel free to contact me if you would like a copy of that data.

In the original version of this blog post, the figure for boys with SEND other than SEMH and the figure for the average boy were the same after rounding.

By my calculations, based on gender alone, we would expect 171 ASD pupils to have been permanently excluded in 2021/22. The actual number is 173. In 2020/21, the number of exclusions for ASD pupils was lower than we would expect based on gender.

A very important commentary, Andrew. Thank you for doing this.