Phonics Denialism and the Education Policy Institute. Part 1.

The EPI asks "What can quantitative analyses tell us about the national impact of the phonics screening check?" and then gives a ludicrous answer.

Last November, the Education Policy Institute (EPI) published a report on the phonics check that really must be seen to be believed. I didn’t blog about it at the time, mainly due to the amount of educational misinformation coming from “respectable” institutions that month. It seemed futile to respond to individual reports.1 However, I think the EPI report deserves more attention because its use of data is so egregious.

The report examined the introduction of the Phonics Screening Check (PSC) in England. This is a short, statutory assessment taken by Year 1 pupils2 to assess their ability to decode words using synthetic phonics. Children are asked to read 40 words — some real and some made up — to check whether they can decode accurately. Those who fail to meet the expected standard are reassessed in Year 2. The main conclusion of the report is that the improvements in the teaching of reading after the PSC was introduced don't count. The way in which this conclusion is squeezed out of data that show no such thing is impressively brazen.

Let’s hear it for the PIRLS!

Of course, it’s never easy to prove cause and effect in education policy. Still, one of the clearest indicators that the Phonics Screening Check formed part of a successful strategy for teaching early reading is England’s rise in an international league table. PIRLS (Progress in International Reading Literacy Study) compares reading standards among 9 and 10-year-olds across countries, as assessed through standardised tests administered to a sample of children.

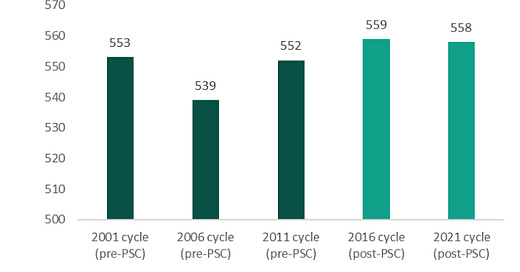

England’s performance in the first PIRLS assessment in 2001 was strong, though marred by sampling issues — over 40% of selected schools withdrew and were replaced. Since then, England has participated properly in the 2006, 2011, 2016, and 2021 cycles. During that time, the country moved from 19th place (out of 45 countries) with a score of 539, to 4th place (out of 43) in 2021 with a score of 558. That timeline overlaps with a renewed emphasis on Systematic Synthetic Phonics in primary schools, which was initiated under Labour and intensified under subsequent coalition and Conservative governments.

The improvement is promising, but it’s hard to pinpoint exactly when or how the gains were made. There are limitations to this data:

PIRLS scores are estimates.

The rankings often include ties.

Some countries fail to meet sampling standards, yet still appear.

The 2021 results were inevitably affected by the disruption of lockdowns.

These considerations limit the extent to which we can claim this conclusively demonstrates the success of England’s pro-phonics policies. Nevertheless, as I argued when I discussed this two years ago, it does show that the predictions made by anti-phonics campaigners were demonstrably wrong.3 I also noted, at that time, the extent to which the impressive increase in England’s ranking was downplayed by those who favoured non-evidence-based approaches to reading.

How the Education Policy Institute presents this data.

The EPI appears committed to ignoring England’s rise up the PIRLS rankings. It presents the following information:

Then it concludes:

Given that the 2021 score is very close to the 2016 score, this demonstrates that there is little substantive variation between 2001, 2011, 2016 and 2021: 2006 is, for whatever reason, the anomalous low.

This analysis is flawed at both ends. Not only does it include the very problematic 2001 results4, it also ignores the impact of the pandemic on the most recent PIRLS data. Other countries’ results nosedived following the pandemic. While England’s fall from 559 to 558 in the most recent PIRLS round might not seem impressive, it seems like quite an achievement when you see that Finland dropped from 566 to 549. Most countries took a significant hit in their results in the most recent round. The median mark fell by 19 points.5 England’s score barely changed, and that looks like a remarkable achievement. It is obvious from England’s journey up the international rankings that this happened, yet the EPI report completely glosses over this fact, which seems more like dishonesty than carelessness.6

To Be Continued…

The interpretation of PIRLS is not the most blatant misuse of statistics in the EPI’s report. In Part 2, I will examine the report’s analysis of Key Stage 1 reading data. This is even more transparently designed to conclude that the PSC has not improved reading despite data showing no such thing.

That same month, the Commission on Young Lives and the IPPR also produced terrible reports on youth crime and exclusions, respectively.

Year 1 pupils are aged 5 to 6.

I wrote two blog posts about PIRLS and what it showed about the claims of phonics denialists:

As I described in this blog post, the 2001 results were very flawed.

While the 2001 result would be interesting if correct, there is good reason to ignore it. England’s score in the 2001 PIRLS report is marked with a couple of caveats, the most serious of which is the extent to which the original sample had to be changed. Of the original selection of schools, only 57% took part in the PIRLS assessment (the target is 85%). The others had to be replaced. The other caveat was to do with coverage of target populations, with 2001 having a much higher rate of “within sample exclusions” i.e. pupils that were originally chosen to sit the PIRLS assessment but were then ruled out. I can’t claim to understand this well enough to know whether this second point is important. Returning to the first point, the replacement of more than 40% of the original sample would be a worry in any piece of research. It is particularly concerning when there is such a big change in results from 2001 to 2006. People might wish to claim that the 2001 result is, nevertheless, accurate. I would be the first to be fascinated if there was an alternative explanation for England’s dramatic decline. However, in the absence of that alternative explanation, I would assume the 2001 result was incorrect.

From page 9 of this document.

It should be noted that Systematic Synthetic Phonics became government policy in the late 2000s. Therefore, the improvement from 2006-2011 can be seen as supporting the focus on SSP, not undermining it.