On Thursday, England's teaching profession will learn whose side the new education ministers are on

If you don't support a school's right to exclude, you can't be on the side of teachers

Teachers are found in schools. For this reason, they want schools to be safe. This means that they support the right of schools to exclude dangerous or out-of-control pupils1. The traditional education establishment is found in university education departments, Local Authorities, charities, and consultancy. For ideological reasons, they do not like adult authority in schools. They want to reduce exclusions at any cost. This week, ministers will have to pick a side.

On Thursday, the exclusion figures for the academic year 2022/23 will be published. To understand these figures, you will need to know what has happened in recent years.

A brief history of permanent exclusions

Permanent exclusions2 reached a historic low point in the school year 2012/13.

This is even clearer if you go back before 2006/07, although the figures are less accurate and I only have raw numbers, rather than the exclusion rate. I didn’t try to go back further than 1997 as the further back you go, the less accurate the figures are.

One day, I hope to do a more in-depth study of the changes shown in the graph. For now, let me make four observations:

It’s unclear to what extent schools and Local Authorities were gaming the system and how this changed over time. The number of children being moved out of schools for their behaviour at any point may have been very different to what the figures show3. Some trends visible in the graph may result entirely from increased or decreased gaming.4

The fall in permanent exclusions during the pandemic is the one feature of the graph that can be easily explained. However, it should be remembered that the period of school closure in the 2020/21 academic year was only six weeks, and it is unclear why exclusions would be even lower in that year than in 2019/20.

There seems to be some connection between the attitude of the government towards exclusions at a given time, and the trend in the figures. What is much less clear is how the attitude of the government affects the figures. There’s no single policy mechanism that determines the level of exclusions.

For all the talk of exclusions rocketing under the Tories (2010-2014), the period of sustained increase was relatively short-lived (2012-2017) and began from a historic low point.

Will the new exclusion figures be high?

Since the pandemic, the Department for Education (DfE) has been releasing termly figures for exclusions. In the autumn and spring terms of the 2022/23 academic year, the number of exclusions was high.

As you can see, there is a lot of fluctuation in termly exclusion rates. While neither term in 2022/23 is a record-breaker, it is the first time there have been two consecutive terms with such high exclusion rates. We don’t know if the summer term will also be very high. There may have been fewer extremely disruptive pupils left to be excluded in the final term of the year. However, we know from the first two terms that the total number of exclusions for 2022/23 will be high. It is plausible that the overall exclusion rate for 2022/23 will be the highest since the 00s. Even if it isn’t, the school population is larger than during the peak level of exclusions in 2016-2019. This means that the number of permanent exclusions is very likely to be the highest since the 00s, even if the exclusion rate isn’t.

Why were there so many permanent exclusions in 2022/23?

Given that we can expect headlines on Thursday claiming exclusions are exceptionally high, it’s worth considering why there would have been a substantial number of exclusions in 2022/23. I can think of four reasons.

There are pupils with extreme behaviour who avoided exclusion in the pandemic years due to lockdowns or absence. Many pupils who would normally have attended AP remained in mainstream5. It is likely that the cohort of pupils in mainstream schools in 2022/23 was exceptionally challenging.6

There was a craze for “toilet riots” that year and other TikTok-inspired incidents of mass disruption. This may have led to more exclusions.

The overwhelming majority of exclusions take place in secondary schools, and between 2016/17 and 2022/23 the number of pupils in secondary schools increased by about 450,000 while the number in primary schools fell by around 75,000.

Pupils who started secondary school during the disrupted years of the pandemic may never have fully acclimatised to the secondary school environment. These pupils may have been particularly challenging as they entered Years 9 and 10 as these are the years when exclusions usually peak.

I would assume there are other reasons too. When the full statistics, including the breakdown by year group, are published, I may reconsider the importance of these explanations. However, it seems likely that a high number of permanent exclusions in 2022/23 was inevitable, and it would not be surprising if the final number was exceptionally high.

What to expect on Thursday

The reasons I gave above explain why exclusions are high due to factors beyond the control of schools. I fear journalists will be more interested in explanations that blame schools and those who have been in charge of them. The change of government means there is also every reason for our new education ministers to condemn the rises and blame their predecessors. There are many pundits who, during the last decade, made claims about the Conservative government, MATs7 and “strict schools” causing sky-high exclusions. If they made these claims when exclusions were at record lows, they will surely make the same claims when exclusions are high.

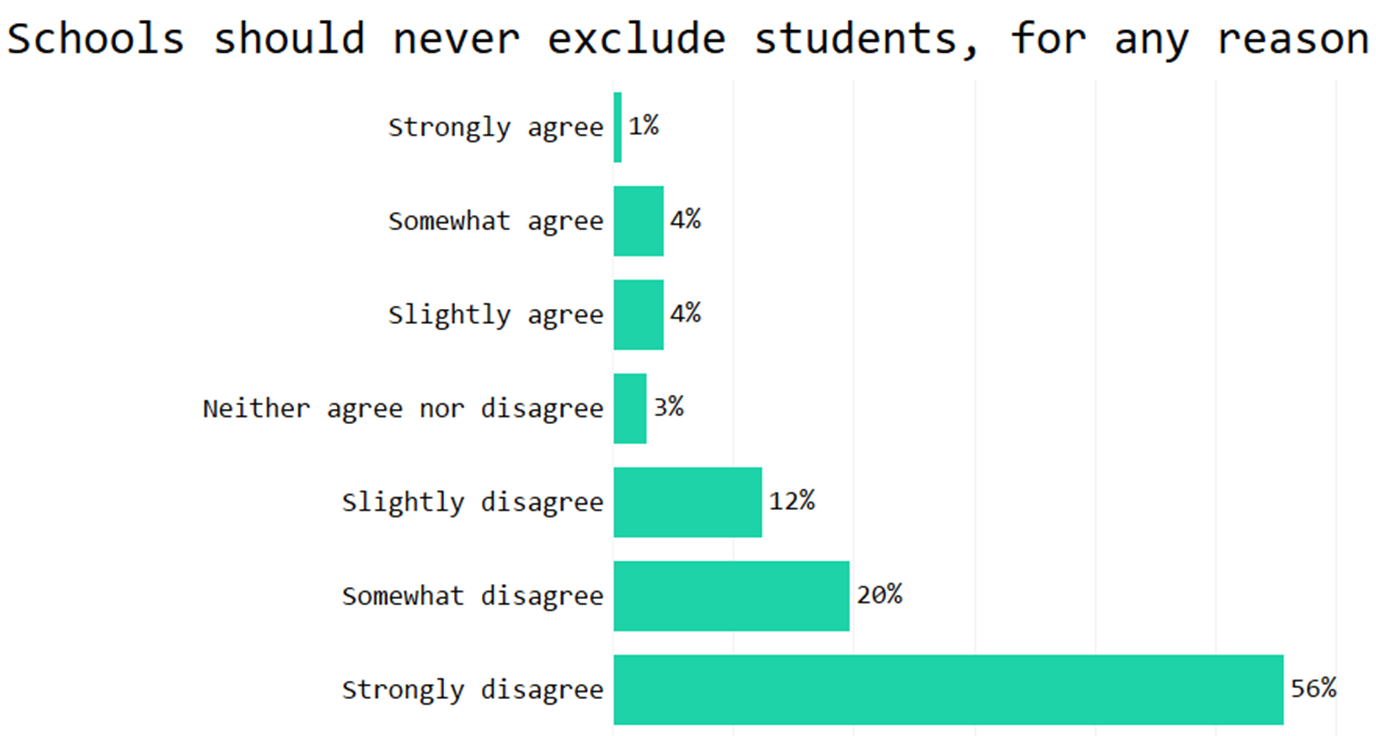

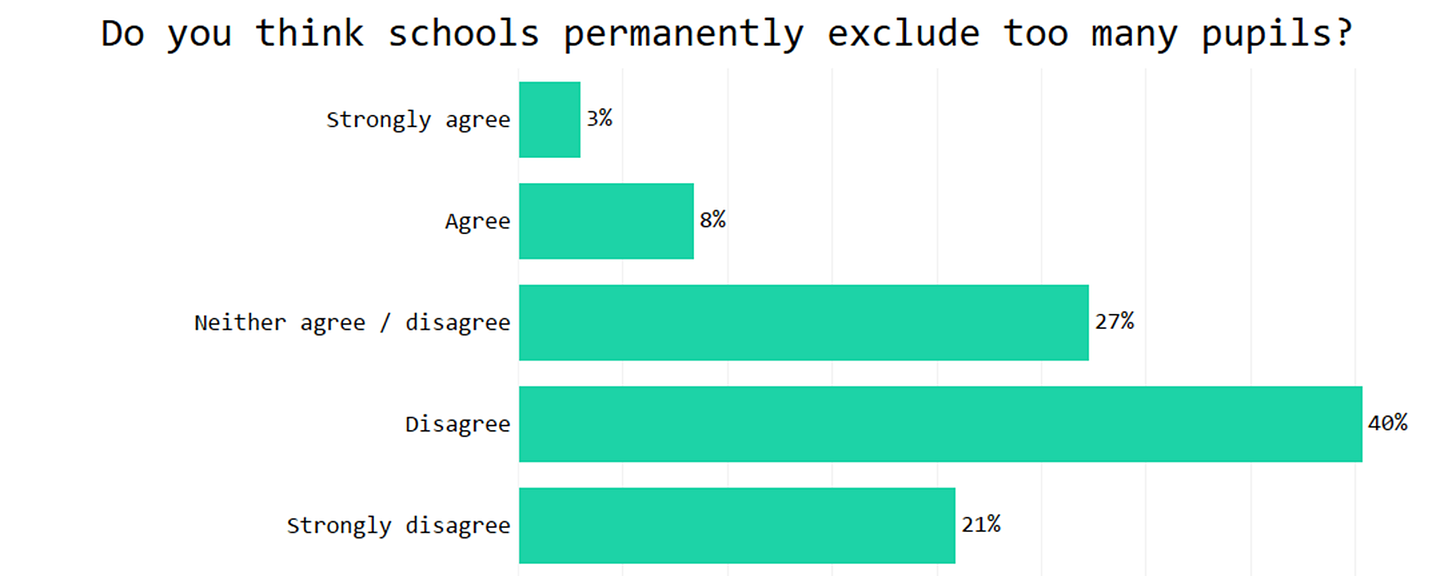

However, what will matter most is the debate about what should be done. Every activist, ideologue and vested interest will call for action to reduce exclusions. The voices from university education departments, hard-left unions, campaign groups, think tanks and Local Authorities will be deafening. No lie about exclusions will go unrepeated in the coming weeks. There will be unprecedented calls for a Scottish-style system of inclusion where schools cannot permanently exclude even the most violent or dangerous pupils. As well as this, pundits will use the figures to justify every opinion they already hold about education. We can expect them to tell us that, because of exclusions, ministers should:

abolish exams;

dumb down the curriculum;

stop schools enforcing rules;

return every school to Local Authority control.

Squeaky bum time8 for teachers

This debate will probably tell us whether the newly appointed education ministers are on the side of teachers and pupils (who need schools to be safe), or the side of the traditional education establishment (who want to reduce exclusions at all costs). While it would be ridiculously optimistic to expect ministers not to use the figures to attack the last government, there is more than one way they can respond. If ministers say they will make it harder to exclude, or claim that schools have done too little to prevent exclusion, we can expect the worst. It will indicate they will make teaching more of a struggle in the next few years. If ministers offer to help schools deal with behaviour, but say they support the right of schools to exclude, teachers can breathe a sigh of relief. Ministerial attitudes on Thursday will tell us if we will be returning to the 00s9 with dangerous schools covering up serious incidents and teachers being gaslighted and silenced about behaviour. What ministers say will also indicate whether the new team at the DfE is listening to frontline staff in schools, or the ideologues in the education establishment. That will tell us a lot about what we can expect in other policy areas too.

This will be a scary week.

Figures for suspensions will also come out. I don’t think these are particularly important, mainly because they are much easier to manipulate than permanent exclusions. I think suspension figures show us only how much schools care about making suspension figures look low.

One method of manipulating figures is “off-rolling”. This is where a pupil leaves a school for reasons that are in the school’s best interests (but not necessarily the pupil). Another method is what I would call “on-rolling”. This is where a pupil remains on a school’s roll while attending specialist provision with little likelihood of returning. In some cases, the specialist provision is the same as it would have been if they had been permanently excluded.

If I remember correctly, the fall in the late 00s and early 10s coincided with the popularity of managed moves, i.e. moving pupils between schools voluntarily. The rise in the mid-2010s coincided, at least partially, with Ofsted clamping down on off-rolling.

More challenging pupils aren’t just a problem themselves. Teenagers are very influenced by their peers, and increasing the number of pupils with extreme behaviour is likely to encourage extreme behaviour in others.

Multi-Academy Trusts

A translation for overseas readers: https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/squeaky-bum-time

I realise that I have warned against returning to the 00s and against copying Scotland. These two options are pretty much the same. Scotland and England adopted the same policies in the 00s. Scotland continued with policies that England abandoned, and now serves as a warning about how weak politicians and an ideologically driven education establishment can destroy an education system.