BBC Radio 4's Law In Action has some very dubious statistics about exclusions from school. Part 2

Do exclusions from school cause knife crime? And how many good GCSEs do excluded pupils get?

The story so far…

A recent Law In Action programme on Radio 4 explored knife crime. The section concerning schools and exclusions was irritatingly incorrect.

Here’s what was said:

Joshua Rozenberg (narrating): … that's not the only problem we see in schools. Just one per cent of children are excluded from lessons because of their behaviour, but amongst those students, four out of ten will end up in prison. Some have been represented by Aika Stephenson, a solicitor at Just for Kids Law. I asked her why excluded children often find themselves caught up in the criminal justice system:

Aika Stephenson: It starts with them being excluded from school, and they begin to be placed on the fringes of society. So, they're not doing what their peers are doing, and they are placed in pupil referral units. Children who have been excluded… I think the statistics are that one per cent of children who've been excluded go on to achieve five GCSE passes, which is essentially what you need to get into college or sixth form. And so, once they've been excluded, essentially they're operating on the fringes of society.

Joshua Rozenberg: Of your clients, youngsters charged with criminal offences, do you have a feeling for how many started being excluded as youngsters when they were eleven, twelve, or even perhaps younger, when they were in primary school?

Aika Stephenson: For me, I mean it's much more rare to actually represent a child that hasn't been excluded. Pretty much everyone in my caseload at times, the route1 has been school exclusion.

Joshua Rozenberg:What you're telling me is excluding a child from normal lessons at school is, or can be, a pathway to crime?

Aika Stephenson: Yes, sadly, and I think there's so much research that supports this view.

Joshua Rozenberg: If you're a school and you've got somebody who's disruptive, the obvious thing seems to be that if they're causing trouble to the other kids in the class, you move them out of that classroom and you give them something different to stop them making life difficult for all the others. But it can have terrible consequences, you're telling me.

Aika Stephenson: Yes, for most young people on my caseload, it can have terrible consequences.

In part one, I examined the evidence about whether offending starts with exclusion from school. In this post, I focus on knife crime and the claim that only 1% of excluded pupils attain five GCSE passes.

Does knife crime start with exclusion from school?

In my previous post, I concluded that the assertion that involvement with the criminal justice system begins with exclusion from school was not true for the majority of young offenders. It is even more misleading in the context of knife crime than for offending in general. A 2018 Ministry of Justice study looked at those young people who were cautioned or convicted for knife possession:

Of those knife possession offenders whose first offence was prior to the end of KS4, approximately 21% are known to have ever been permanently excluded from school. Of these, there is an approximate 50/50 split between those whose first exclusion was prior to the offence, and those who were excluded at some point after the offence (and a small proportion [3%] where the offence date and exclusion date are on the same day).

The report concludes that:

…it is not possible to identify whether there is an association between exclusions and knife possession offending, and that the low volumes of knife possession offences following exclusions mean any such association could not be a significant driver of youth knife possession offending overall.

This observation was also repeated in the Timpson report on school exclusions. Any journalist familiar with the issue of school exclusion should have been aware of this.

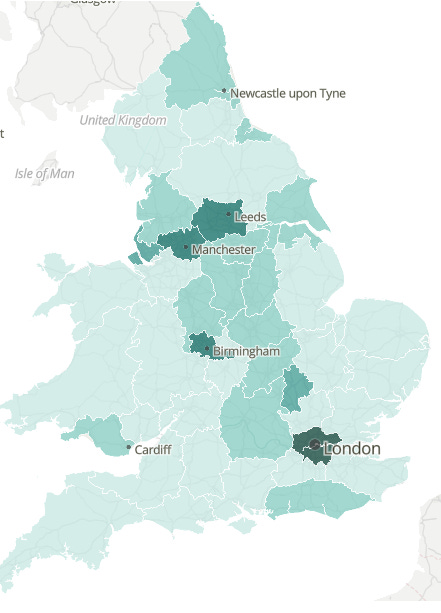

Another reason to doubt the idea that school exclusions are a major driver of knife crime is where knife crime occurs. The Office of National Statistics produced a map of where knife crime occurs in England and Wales, where the darkest areas show the highest knife crime rates.

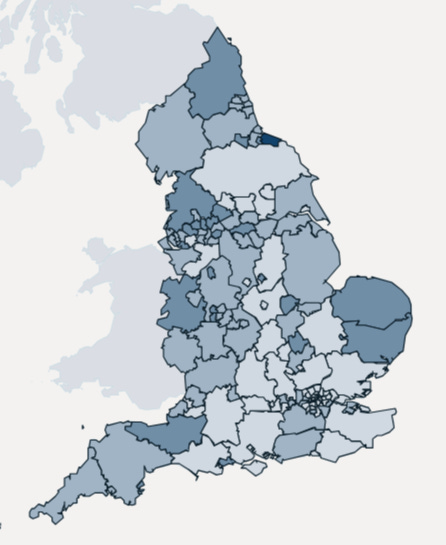

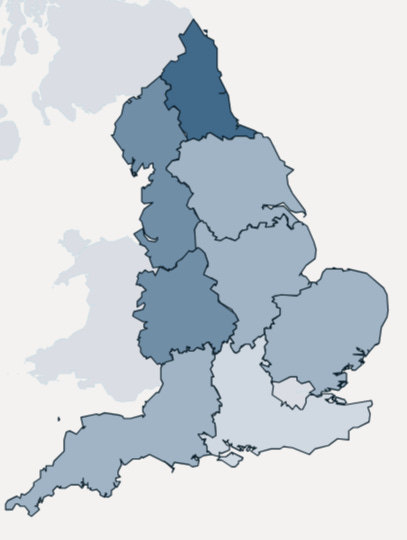

The DfE produced a map showing where school exclusions occur in England. The darkest areas show the highest exclusion rates2.

This does not suggest knife crime in England is driven by exclusions. London is a striking counter-example, as it is the centre of knife crime and has the lowest exclusion rate.

In the last couple of years of exclusion data, we have acquired new data relevant to the connection between knife crime and permanent exclusions. Since the 2020/21 academic year, exclusion and suspension figures have included the category “Use or threat of use of an offensive weapon or prohibited item”. For permanent exclusions, this is likely to mean carrying a knife. In 2020/21, this was a reason given for 540 permanent exclusions out of 3928 permanent exclusions (14%). In 2021/22, it was a reason given for 549 out of 6495 exclusions (8.5%)3. This indicates that carrying a knife often happens before, rather than after, exclusion. Again and again, we find that knife crime cannot be explained by permanent exclusion.

Excluded pupils and GCSEs

Aika Stephenson also claimed that “one per cent of children who've been excluded go on to achieve five GCSE passes, which is essentially what you need to get into college or sixth form”. Teachers reading this will know that this measure of achievement is somewhat outdated, with schools now using Attainment 8 and Progress 8 to evaluate academic performance. Even before Attainment 8 and Progress 8, it would have been usual to state whether the five GCSE passes included English and maths4. Still, is this statistic true? Of course not.

I have heard this statistic before. Annoyingly, I hadn’t previously checked it, even though it comes from a source riddled with false information. In 2017, the IPPR, a previously credible think tank, produced a report arguing against exclusions. It included obvious falsehoods like claiming permanent exclusions cost £370000 and almost 100% of excluded pupils have mental health problems. It also claimed that “1 per cent of excluded pupils get the five good GCSEs they need to access the workforce”. No source is given for that claim, but subsequently, it states “Only 1 per cent of excluded young people achieve five good GCSEs including English and maths” and there is a source for this statistic. It is claimed it comes from the GCSE tables for AP (Alternative Provision) from 2015/165. However, the figure on that table is not 1%, but 3.4%. And even if it had been correct, the figures for pupils in AP are not the same as those for excluded pupils, as not all excluded pupils attend AP. I am beginning to wonder if anything in that IPPR report is correct.

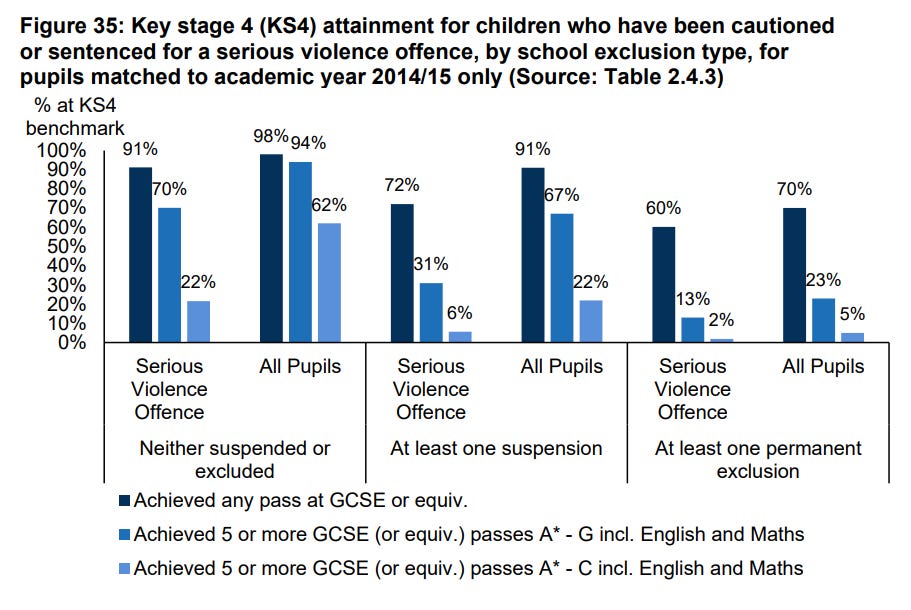

Of course, one might be tempted to think that it doesn’t matter. 3.4% is still low, and there is an overlap between excluded pupils and pupils in AP. Is it the case that exclusion causes pupils to fail their GCSEs, and this leads to their criminality? The MoJ/DfE report on the backgrounds of young offenders, which I mentioned in my previous blog post, shows a more complex picture (and a different pass rate).

From this we can see:

5% (not 1%) of excluded pupils got 5 or more A* to C passes including maths and English;

Only 2% of those cautioned for serious violent offences and permanently excluded achieved 5 or more A* to C passes including maths and English;

Those who were cautioned or sentenced for a serious violent offence and were not permanently excluded had much worse results than the average pupil.

Permanent exclusion is correlated with worse GCSE results and violent offending, but a correlation between GCSE results and violent offending would exist without permanent exclusions. We already knew that the claims about exclusions leading to offending were overblown. Now we know the data does not support the claim that GCSE results were the mechanism by which exclusion led to offending.

And, of course, young people are now meant to stay in education and/or training until the age of 18, regardless of whether they get 5 good GCSEs. While GCSEs are important, it is ludicrous to suggest that all those who miss out on this particular benchmark are on the fringes of society.

I won’t pretend to be surprised at Radio 4 reporting activist talking points as facts. But I am disappointed.

Quoting this a second time, it occurs to me that Aika Stephenson could have been saying “root” (i.e. the root cause) rather than “route”. I don’t think this has any implications for my argument.

More than one reason can be given for an exclusion. The DfE gives the percentage of exclusions where a particular reason was given as a percentage of the reasons, not as a percentage of exclusions. This is why I calculated my own percentages above.

And if you want to be fussy, “pass” is a rather ambiguous term when it comes to GCSEs. Anything other than a U is technically a pass.

It can be found on this webpage.