The problem with interventions for mental health and behaviour

Debates about what we should do can distract from debates about what we can do.

Debates about the purpose of education can lead us astray

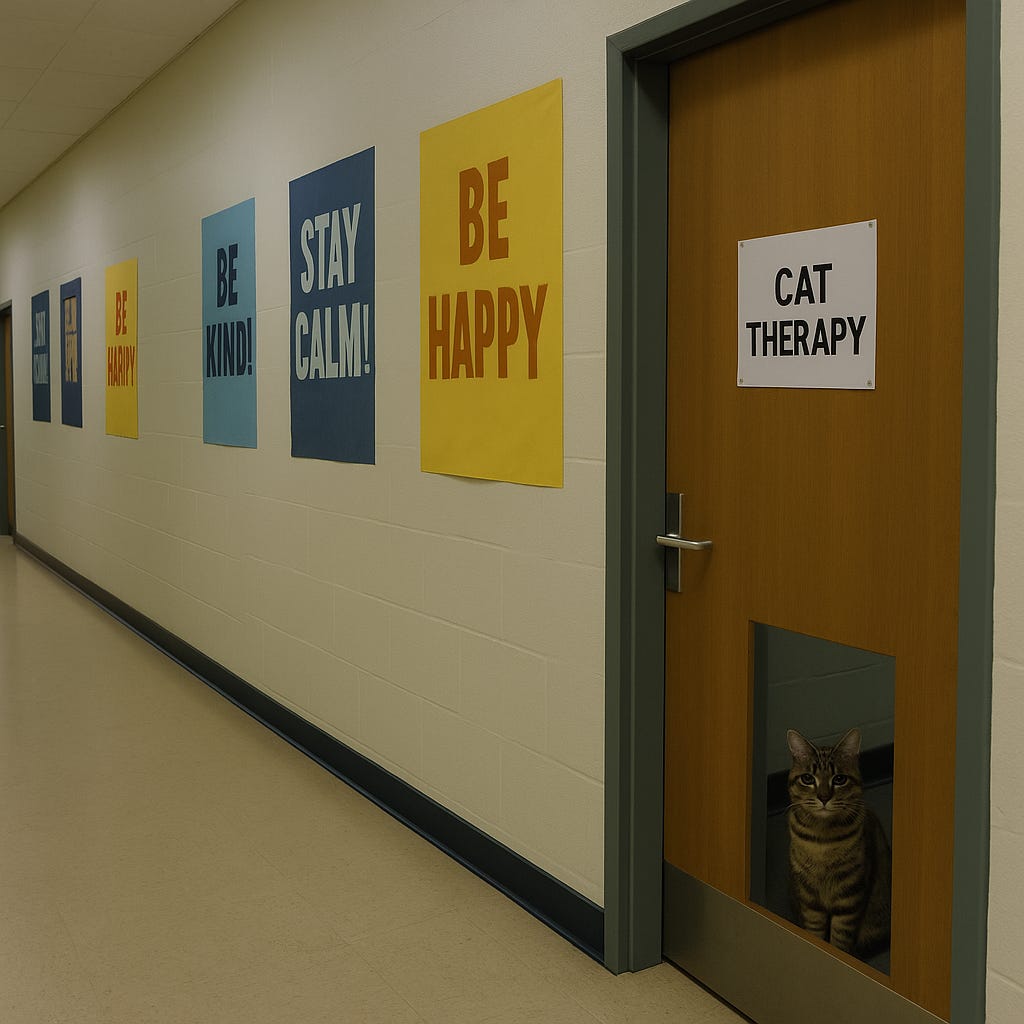

A lot of "debate" about education involves suggesting new purposes for educational institutions. These are invariably aims that seem worthwhile, but are possibly not the primary aims of schooling. One example of this is the way people become invested in the idea that the purpose of education is to promote happiness or character formation. It seems problematic if being educated results in lifelong misery or moral corruption. However, it's unclear to what extent education should be expected to result in good feelings or moral righteousness. Even if these are seen as legitimate aims of education, there is still the possibility that they are aspects of a child’s upbringing that are primarily the responsibility of families and communities.

I mention this, not because I wish to resolve or discuss it now, but to provide context for why people may make assumptions about the responsibilities of schools that are open to being contested. If schools are meant to make sure pupils are happy, we might assume that schools should be responsible for achieving good mental health for their pupils as a high priority. This might be contrasted with the view that while schools may be well-placed to seek help when serious mental health problems occur, they are not fundamentally therapeutic institutions. If schools are meant to encourage good character, we might assume that they should be able to rehabilitate those who are showing bad character or exhibiting harmful behaviours. This could be contrasted with the view that schools are not designed for rehabilitation. Of course, schools may be responsible for preventing bad behaviours and are well-placed to seek help when pupils’ actions are seriously harmful. However, determining the moral character of their pupils might be more of a struggle, and curing a personality disorder would almost certainly be impossible.

I say all that to acknowledge that there is debate over the extent to which ensuring good mental health and rehabilitating the badly behaved are responsibilities that schools should undertake, and how much priority should be given to them. There is also some conflation between the two, with some seeing bad behaviour mainly as a matter of mental health and therapeutic interventions as the best form of behaviour management. All of this tends to shape the debate so that we end up discussing the extent to which schools should act to improve mental health and the motivation to behave, rather than the extent to which they can. This is important because scepticism about the effectiveness of interventions in these areas is often treated as scepticism about the importance of mental health, or encouraging good character, and dismissed on those grounds. However, while I am somewhat sceptical about how much schools should be attempting to be therapeutic or rehabilitative, most of my scepticism is about whether such attempts actually work.

The problem of interventions that don’t work

For one moment, let’s ignore the debate about whether schools should be providing dramatic mental health and behaviour interventions. That still leaves us with the biggest problem: the lack of good evidence that these interventions are effective. Worse, some mental health and behaviour interventions may be harmful. This is a reasonable concern that stems from a more general worry about the effectiveness of many psychological treatments. Scott Lilienfeld, in a memorable 2007 paper, "Psychological Treatments That Cause Harm", discussed "Potentially Harmful Treatments (PHTs)". This paper should be required reading for anyone planning to intervene to improve a pupil's mental health. In one section, Lilienfeld examines the outcomes of meta-analyses for therapy in general.

Negative Effect Sizes in Meta-Analyses

Second, meta-analyses of treatment outcome consistently reveal negative effect sizes in a notable minority of studies. For example, the seminal Smith, Glass, and Miller (1980) meta-analysis of 475 therapy outcome studies revealed that 9% of effect sizes were negative. Some subsequent meta-analyses revealed comparable or perhaps slightly higher percentages of negative effect sizes (e.g., Shapiro & Shapiro, 1982), and a meta-analysis of studies of treatments for adolescent behavioral problems indicated that as many as 29% of effect sizes were negative (Lipsey, 1992; see also McCord, 2003, and Rhule, 2005). These numbers raise the distinct possibility that certain psychotherapies are harmful to some individuals.

It is worrying to think that therapies that were analysed in this way could have negative effects. We would expect therapies included in this sort of analysis to have been developed by experts in line with sound psychological theories. If some methods developed by mental health and psychology professionals have made things worse, what can we expect when education professionals, who may have limited training in mental health, use therapeutic methods?

Some of the harmful therapies that Lilienfeld identifies might well be relevant to educators. Some, such as "Attachment therapies", are aimed at children. Others are treatments for "conduct problems" and are likely to overlap somewhat with methods used to address behaviour issues in schools. One is a talking therapy used to prevent the symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, which seems relevant given the current fad in education for "trauma-informed" approaches. Lilienfeld also notes that "school-based prevention programs for antisocial behaviors, such as school counseling that is not cognitive-behavioral in nature... produce harmful effects in at least some individuals" but doesn't include that in his main list of PHTs because of a lack of independent replications.

Sometimes it’s better to do nothing, than to do the wrong thing

There's an obvious question here as to what extent those recommending interventions for behaviour or mental health problems in school are aware of the issue of Potentially Harmful Treatments. In my experience, I have seen countless people who work in education justify interventions by simply saying that they are "trauma-informed" or based on "attachment". Many of those advocating these approaches imply that there will be disastrous consequences if one is not "trauma-informed" or one doesn't address attachment difficulties. These arguments tend to assume that it is better to try such interventions than to do nothing, even if there is currently no strong evidence for the effectiveness of these interventions. I find it hard to believe that such an argument could be made sincerely by somebody aware that some interventions could prove harmful or that they could be worse than doing nothing.