I had been hoping to avoid writing more about the Observer’s bad education journalism. Nobody at that paper seems to care that its education stories are ideological set-pieces, strung together with misleading or false information, so why should I? But this weekend it reached a new low with a story about an inspiring headteacher turning around a school1. Most of what was said in the article seems to be untrue.

If only the Observer’s journalists had been reading my blog this week

Before I get onto the main details of the story, I’ll start with some familiar territory. Earlier this week I published a two-part story about two dubious claims spread by London’s Violence Reduction Unit.

Blog Post Series: Claims about crime and exclusions from London's Violence Reduction Unit

These posts examined claims that excluded pupils are twice as likely to carry a knife and that half of prisoners have been excluded from school. The second post indicated which media outlets had reported both statements as facts, after they were spread by London’s VRU. The Observer’s latest education story has joined the hall of shame by repeating both claims:

Lib Peck, the VRU’s director, says kids out of school are twice as likely to carry a knife. “They might get caught up in a gang or exploitation. They might just think a knife will make them safer. We know it will put them more at risk.”

There is also evidence that children excluded from school are more likely to commit crimes when they are adults. One in every two people in prison were excluded as children, according to research by the Institute for Public Policy Research thinktank.

That’s shoddy work, but the rest of the Observer’s article is worse.

Some headteachers cope with crises by seeking good publicity

The Observer focused positively on a school doing what the VRU wants, i.e. saying negative things about exclusions. The BBC took the same approach. However, while the BBC gushed about a primary school, the Observer selected a secondary school and this makes the reporting a lot easier to fact-check. Much of the Observer’s story is based on statements made by the school’s headteacher. Many of those statements are not true.

The headteacher’s narrative is that the school used to be in crisis, but that he has turned it around. It reports that he arrived at the school in 2018 and felt it was “very tense”.

…the fifth head at the school in three years, was faced with “the most stark anti-school feeling” he had encountered in three decades working in London state schools.

“There were more children in the corridors than in the classrooms,” he says. “Parents didn’t want their kids to be here.”

Six years on, the school has an unexpected air of calm. Pupils, who come mostly from three deprived housing estates nearby, say it is no longer frightening.

The claim that “Parents didn’t want their kids to be here” was also in the headline. It may well be the case that the school was unpopular in 2018. However, the implication that in the years since 2018, parents have wanted to send their kids to the school is not as plausible. The school roll has fallen catastrophically.

According to a recent news report, the school is in the process of reducing its places in Year 7 from 180 to 120. To have been offering 180 new places each year, and still have only 381 pupils in total in all five years, the school must have been very undersubscribed. And this does not appear to be a temporary blip. Of those 381 pupils, 86 sat their GCSEs in 2023, indicating that the departing year group was larger than the average size of the other year groups. Also, the average year group size is smaller in Key Stage 3 than in Key Stage 4. Even without that worrying trend, an ordinary, 11-16 secondary school in London with 381 pupils can probably be considered to be at risk of closure. Perhaps, the desire to attract new parents to consider the school might explain some of the claims the headteacher makes about his school.

The headteacher has turned the school’s results around, hasn’t he?

According to The Observer:

GCSE results at the school have been steadily climbing from what [the headteacher] calls “absolutely atrocious” in 2017 to just below national average now (he thinks they will hit that milestone in a year).

Even minimal research would have shown that the school does not have results “just below national average”.

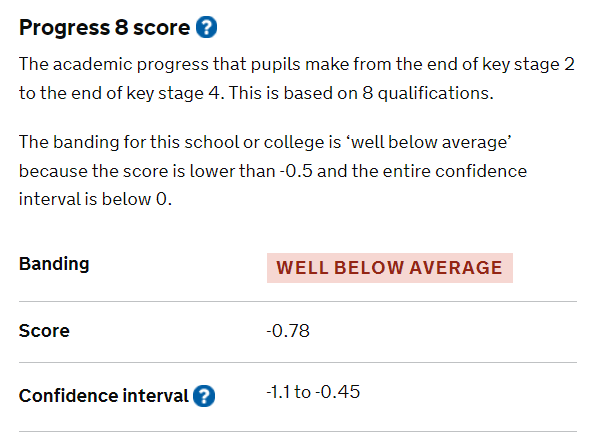

This is bad, but could it still represent an improvement? It is not simple to extract Progress 8 scores for previous years from the DfE’s spreadsheets (and the school has changed its name), but I found the relevant P8 scores. (I have not constructed a graph this time as exams were not taken during the lockdown years of 2020 and 2021).

Progress 8

2017: -0.32

2018: -0.72

2019: -1.01

2022: -1.08

2023: -0.78

No other statistic seems suitable for comparisons between years as national pass rates changed dramatically in 2022 and 2023. As you can see, the school’s P8 results do not resemble the head’s story of atrocious results in 2017 and improvement after he arrived in 2018.

The headteacher has turned the school’s behaviour around, hasn’t he?

By 2023, the school had shrunk to the point where it had 10.9 pupils for every teacher, compared with a national average for secondary schools of 16.8. In theory, this should give it a massive advantage when it comes to behaviour. On top of that, it was reported last year that the Evening Standard had funded the school’s inclusion unit. Any school with so few pupils and extra cash for removing and supporting its most challenging pupils should be able to do great things in managing behaviour.

The Observer’s article has many positive things to say about behaviour, and Ofsted also improved their rating of the school’s behaviour between 2019 and 2022. I have no reason to doubt that behaviour has improved. Nevertheless, the Observer’s story still appears to have created a misleading narrative about behaviour.

…in 2018 the whole place felt “very tense”. Violence was a serious problem and there were 300 suspensions a year as staff wrestled to control it…

…But far from pushing out anyone deemed to be disruptive, [the headteacher] has instead ushered in an era where “everyone is included”. Suspensions last year were down to 25, only one child was permanently excluded and these sanctions were a last resort after staff had tried everything else first…

…The attempt to drive down exclusions has some fierce detractors. They include the government’s own behaviour tsar for England, Tom Bennett, a vocal supporter of tough discipline and silent corridors.

Last summer, he wrote in the Spectator about {Mayor of London, Sadiq] Khan wanting to reduce exclusions, announcing: “London’s schools are about to become less safe.”

[the headteacher] is quick to point out that his school was far less safe when suspensions were really high. He describes Bennett’s comments as “the sort of unevidenced thing you hear from people who haven’t actually spent time teaching in schools”.

Tom Bennett, of course, spent more than a decade teaching in challenging schools before working full-time as a behaviour expert and advisor. More importantly, there is little evidence to suggest that the school is doing anything regarding behaviour that Tom Bennett would object to2. There is also little to suggest the school is doing anything different from many other secondary schools. The figures show reductions in exclusions and suspensions, but not to exceptionally low levels. In 2021/22, the school’s exclusion rate was 0.47, compared with a national average for secondary schools of 0.16, although in such a small school we would expect the exclusion rate to fluctuate. The suspension rate in 2021/22 was 14.49 compared to the national average for secondary schools of 13.963. However, given the Observer claims the school is supporting attempts to drive down exclusions and suspensions in London, perhaps national figures are not the relevant comparison. In Inner London, where the school is located, the exclusion rate for secondary schools in 2021/22 was 0.07, and the suspension rate was 9.56. This would suggest the school’s approach to exclusions and suspensions is closer to Tom Bennett’s than Sadiq Khan’s.

The article also gives examples of rules being enforced and children being sent to a “refocus” room (complete with booths) for three days. The article, showing no apparent knowledge of what is typical in schools, finds weak excuses for claiming this is different to the “strictest academy chains”. Any teacher reading this article would not find anything in it particularly different from other schools with a functioning behaviour policy, even the majority of schools in the “strictest academy chains”. Defaming Tom Bennett and attacking his views on discipline is political rhetoric, but it doesn’t seem to reflect what the school is doing.

A new low for The Observer

The Observer’s story seems to have created a completely false narrative about this school. It has poor results and falling rolls, and if behaviour has improved, it does not appear to be because it avoids exclusions and suspensions, but because it has very few pupils; considerable outside resources, and an approach to behaviour based on exclusions, suspensions and removal. Even by the low standards the Observer has set recently for bad education reporting, this story stands out as inaccurate and misleading.

I have not mentioned the school, or the headteacher, by name in the article, even though it is identifiable from the links. This is because I do not want this article to come up when people search for the names of the school or the headteacher. My aim here is to challenge bad journalism, not to shame a school.

A possible exception to this is the head’s claim to have identified “trauma” in three-quarters of the school’s pupils. No reputable behaviour expert would claim this is an appropriate activity for schools.