Matt Damon was wrong

A few years ago, my local Odeon repeatedly showed me the trailer for "We Bought A Zoo". After seeing the trailer, I realised I would be no more likely to watch this film willingly than I would intentionally contract scabies.

However, one line from the trailer stuck in my mind:

"...you don't even need a lot of special knowledge to run a zoo. What you need is a lot of heart".

This stuck in my mind because you do need a lot of special knowledge to run a zoo. For instance, if, like the late John Aspinall, you don't know that you shouldn't encourage zookeepers to come into close contact with dangerous animals, then you might end up with a lot of maimed or dead zookeepers. Alternatively, if you don't know how to keep animals secure, you may end up with an escaped monkey.

When you think about it, schools are a lot like zoos. But with maths lessons instead of giraffes

The sentimental, but obviously false, belief that how much you care is more important than knowing what you are doing is not limited to Hollywood depictions of zoos. It's a staple of criticism of schools. There are few easier pieces of advice to give, and few harder to follow, than to tell somebody to care more. Schools reverberate with stock phrases about nurturing, relationships, empathy and unconditional positive regard. These statements are generally patronising and vapid. They become harmful when it is suggested that they are more important than having systems in place to protect and support children.

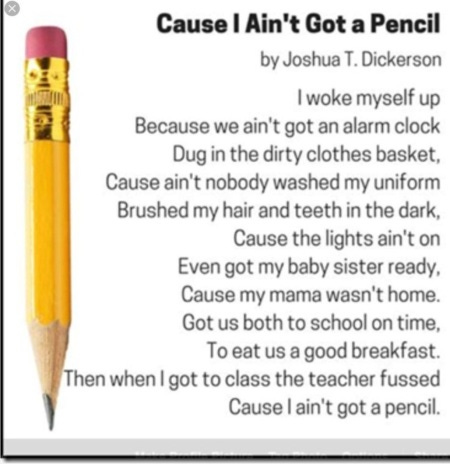

As I mentioned in this post, public expressions of compassion for children are often more about how adults feel than about the best interests of children. What matters is what you do, not how you feel. Yet, people can describe situations where children are suffering neglect and disadvantage as if the problem was that their teachers didn't sympathise enough. Anti-discipline rhetoric (including the "poem" mentioned in that blog post) often describes neglected children as needing exemption from basic expectations, not the immediate intervention of social services.

There is a tension here. Some of what schools expect from children is undermined by chaotic, neglectful or abusive home lives. So there is a temptation to say that children from the worst homes cannot do what others do. But the advantage to the child of a culture of low expectations is far from clear. A terrible home life cannot be compensated for by low expectations at school. It might make matters worse. If schools accept that children from some backgrounds will be unable to achieve or prosper in school, then they won't.

Essential systems

I don't think that poem is the exception. People frequently talk, often in vague or counter-productive ways, about serious school issues as if they were just a matter of teachers being compassionate. Empathy is not enough. Schools need to have systems for some things that simply cannot be left to feelings.

Safeguarding. When there are signs that children are neglected or abused sympathy is not enough. Nor should it be left to teachers to act only when they feel sorry for the child. Safeguarding concerns must be recorded and referred to the appropriate agencies consistently and efficiently.

Discipline. Schools need to set rules and enforce them, not act based on personal impressions. If a rule is only enforced when a teacher feels the pupil breaking it has it coming, it's not a rule. It's barely even a guideline. It will, however, make it more likely that the rules are applied in an unfair or discriminatory way.

Mental health. It may be the case that we see too many things through the lens of "mental health issues". What shouldn't be open to debate is that teachers are not therapists or psychiatrists. Again, there must be systems for reporting and referral to actual mental health professionals.

Judge not, lest ye be judged

Another way in which we should not be motivated by feelings rather than systems is in our responses to different ways of doing things. Something we often see in online discourse is schools or teachers being attacked for doing things their own way. An unfamiliar acronym for helping children pay attention, or a well-regulated procedure for transitions between lessons, is all it takes to set some people off. It is understandable (if not excusable) when people who know nothing about teaching object when they see rules they don't understand being enforced. It is far harder to understand why some teachers get irate when they see unfamiliar rules being enforced. If I don't use SLANT, or my school doesn't have silent corridors, then there must be something wrong with SLANT or silent corridors. As far as I can tell, this is purely an emotional reaction. When I ask people why one set of expectations or procedures that work is morally scandalous when compared with another more common alternative, you get nothing coherent. If it doesn't feel right, then it must be wrong. And if it is wrong, then it can be declared with no evidence that the teachers implementing the procedure have sinister motives; that the procedures are the first step to fascism, or that children's mental health is harmed by the procedures. All three of these arguments can be advanced without any evidence at all; they are just based on "vibes". Some people, when asked about alternatives to a given rule or routine will even claim that if a teacher was competent or a school was well run, there would be good behaviour without the use of that rule or routine. And when you ask them how that would happen, they cannot tell you.

Our feelings are not the best guide to how a school should be run, and a terrible guide to how we judge whether others are running schools in a good way. But I don't think we can, or should, turn into "desiccated calculating machines" who only consider empirical outcomes when attempting to make moral judgements. In my next post, I will discuss when we should, or should not, base our ethical deliberations on our emotions.

If you haven’t already, please subscribe to receive my upcoming blog posts.