Do 97% of pupils excluded from primary school have SEND?

No, it's a bit lower than that. And this doesn't tell us anything about whether they should have been excluded.

For some time now, I have been working on a post about the difference between primary and secondary school exclusions. However, before I finish that, I need to address a new myth about exclusions that’s appeared in the last few days.

According to the anti-discipline campaign group Chance UK:

The statistic is wrong, but understanding why it is wrong requires knowledge of our SEND system. The fundamental difficulty in understanding the system is that the term “SEND” is used in two ways. Sometimes it refers to children with specific (often life-long) conditions, such as autism or a hearing impairment. Sometimes it refers to pupils who need support and are, perhaps temporarily, included on the SEND register to help with the provision of that support. I would strongly agree that children with the worst behaviour need support. However, the practice of placing the worst behaved children on the SEND register, usually in the category of Social, Emotional or Mental Health (SEMH) needs, causes serious confusion. It leads to widespread myths such as the following:

Having SEND often causes children to behave badly.

“Meeting needs” is an effective way to manage behaviour.

Badly behaved children are likely to have a (possibly lifelong) disability or condition.

The reality is that a significant proportion of “children with SEND” may be suffering temporary difficulties with behaving or learning and have very little in common with those who have a disability (in the ordinary sense of the word) or lifelong condition. Confusion is also exacerbated by the lack of a consistent set of standards for who should be on the SEND register, which means that whether or not a child is labelled SEND can depend on their school or their parents, rather than the child.

Once this is understood, we should recognise that:

Children move on and off the SEND register.

Badly behaved children will often be on the SEND register because they are badly behaved.

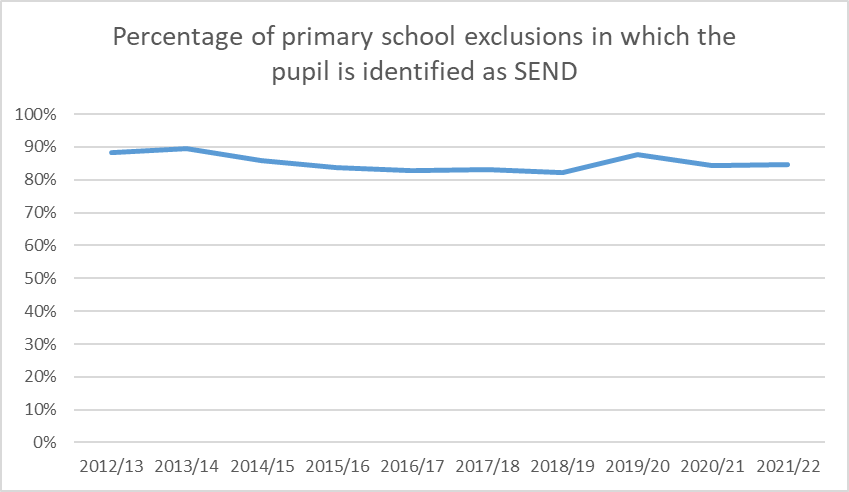

This brings us to the Chance UK claim that “97% of those excluded/suspended at Primary school had a special educational need or disability”. It is not the case that 97% of pupils excluded from primary school are on the SEND register. The vast majority of pupils excluded from primary school are categorised as having SEND, so this is not massively wrong. However, it is an exaggeration. The real figure is usually below 90%. The graph below shows how this statistic has varied over the last 10 years (calculated from here).

This does not represent excluded pupils in general, as most are excluded from secondary schools. Primary schools exclude extremely rarely. At the 2021/22 exclusion rate, we would expect the average primary school to permanently exclude one pupil every 22 years. However, the figures in the graph above do suggest that when extreme behaviour occurs in primary schools, pupils are particularly likely to be identified as having SEND.

Where does the 97% figure come from? It is based on research by FFT education datalab. However, they did not find that “97% of those excluded/suspended at Primary school had a special educational need or disability”. They found that 96.9% of pupils permanently excluded from primary schools were identified as having SEND at some point between reception and Year 6. I cannot explain why Chance UK said “excluded/suspended” rather than excluded. As for the claim they “had a special need or disability”, the most charitable explanation is that they see SEND as an immutable characteristic of the child. If so, they might consider a child who is categorised as having SEND at one point as having SEND at the time of their exclusion even though the data doesn’t show this. However, this will substantially inflate the figures. Even among those who are never suspended or excluded in primary school, 30.4% meet this criterion. I would guess that it is even higher for the demographic groups that are often found among the excluded (e.g. boys, FSM pupils and white British pupils).

Of course, this might seem like nitpicking to those using the 97% statistic to argue against exclusions. Does it matter that much if the proportion of excluded primary pupils on the SEND register is 97% or, say, 85% like in 2021/22? I think a case can be made that while it tells us something about either the honesty or comprehension skills of Chance UK, it makes relatively little difference to many arguments that might be based on the figure. However, this claim will encourage people to think that SEND causes bad behaviour, rather than that children are identified as having SEND because of their bad behaviour. The detailed figures are far more interesting than the false statistic.

Here is what I noticed:

Only 26.4% of pupils who were excluded in primary school are recorded as attending a mainstream secondary school in Key Stage 4. This suggests that rather than being excluded because their primary school didn’t want to support them, exclusion may have been intended to help them access support that would be best provided outside of mainstream.

17.6% of pupils excluded from primary schools had no identified SEND in the academic year in which they were first excluded. Of those who were identified as SEND in the academic year they were excluded, the majority were identified as having needs either in the “Social, emotional and mental health” category or its predecessor “Behaviour, emotional & social difficulties”. In the following year, the majority of those excluded pupils with no identified SEND were identified as having SEND. Additionally, a large proportion of those in every category had their primary SEND category changed to SEMH.

By the time they reached secondary school, 58.8% of pupils excluded from primary school were in the SEMH category. 16.8% had no SEND identified. 10.6% were identified as having Autistic Spectrum Disorder. Other types of SEND don’t appear greatly different from the general population.

Excluded primary school pupils are a small and unusual population. As we have seen, they can expect to be labelled SEND at some point. However, we have also seen that this is not necessarily permanent, and that most excluded pupils with SEND have SEMH as their primary need. This is a category often used for those with behaviour problems. This suggests that we should not see SEND as a cause of the behaviour that leads to exclusion, it is often more of a description. And if SEND can be a label that identifies terrible behaviour, rather than a disability, it is worth reflecting on what kind of behaviour results in exclusions from primary schools. In recent years, exclusion figures have allowed schools to give more than one reason for a permanent exclusion. Around half of primary school permanent exclusions include assault against an adult as a reason. Knowing this, I would argue that there can be a strong case for removing such pupils from mainstream schools for the safety of others. I do not believe that the SEND label, properly understood, changes this equation.